Hollywood hates Weird: The Strange Normalization of Abstract Stories

Ever since the ad campaign for the second season of House of the Dragon started, I got the increased feeling, that at least some of the people responsible for the show, didn`t quite get the story they were telling or rather were supposed to tell. And I don`t mean this as a book purist who spends hours on end ramnling about how the book is better, but rather with a critical look on how adapting a story into a more mainstream medium serves to dilute it. This in itself is not a new critisism, as long as adaptions into movies and shows existed, the question of change has always been at the forefront. Even The Lord of the Rings in all it`s acclaim has regular discussions surrounding it on whether or not it lives up to the epic story Tolkien was trying to tell.

House of the Dragon however serves as an interesting case study on how inserting one`s own ideas clash with the direct source material. Even George RR Martin, the author himself, has recently made headlines, proclaiming immense disappointment and lack of understanding for the series, asking himself, if changes are ever truly warranted or if they just dumb down whatever story they want to tell. This, in my opinion, is the same internal discussion I had, while watching the hugely sucessful Dune: Part 2, a movie, that at least in my opinion, falls flat on its face, whenever it wants to pick up themes of the book.

One major throughline I`ve seen throughout the years, whenever it comes to adapting something to screen, is the absence of weirdness, an inherent refusal to ever show anything that is deemed to „out of place“. Be it leaving out Tom Bombadil in LOTR, the change to the end of Watchmen, whatever is happening with Netflix The Witcher as well as the live-action version of The Last Airbender and even Game of Thrones, which, as the years went on, ever so quietly eliminated all magical aspects of its world until even the biggest threat of the show, the literal ice-zombie apocalypse, was nothing more than an hour long nuissance in the third episode of season 8.

I`ve been long sick of discourses surrounding „filler“ and „irrelevant scenes“, but especially when it comes to Fantasy and Science-Fiction. This is because, as much as some people don`t want to admit it, these genres are weird, they have to be. Creating whole new worlds or a whole future, takes time, it takes work. Writing so that your reality is not just a medieval version of your world but sometimes a dragon shows up is an often times grueling process that demands a lot. Combine that with internal consistency, a society that needs structure and depth, and a story that wants to bring a point across, you have your hands full.

Martin does this perfectly, juggling all this pressure with an almost enviable calm, creating a rich and complex world, that reguarly deals with political themes, class and most important, the horrors of war. Even though both A Song of Ice and Fire as well as Fire and Blood tell the story of noble houses, they never lose focus on the rammifications on the „Small Folk“ as Martin calls them. It is very clear, that despite any sympathies you might have towards a Lannister, Targaryen or a Stark, in the end the political games only hurt everyone. ASOIAF`S fourth book A Feast for Crows deals with the impact the „War of the Five Kings“ has upon the peasants, the whole book essentially being an Odyseey of multiple charactes traveling through ravaged lands and destroyed towns, meeting broken people and encountering a lot of death along the way. When it comes to war, no one wins and even when you think your cause is just, you often times only further suffering.

The problem specifically with House of the Dragon in this regard is, that it obmits these themes from the show and circeling back to the ad campaign, makes a spectacle out of it. Choose a side, they say, be Team Black or Green. That the Dance of the Dragon, the story underneath it all, is a story about two sides of a royal house, that for the sake of power, lay waste to the entire country with what bascially amounts to nukes with wings, only to end with ruin and the beginning of the end for the Targaryens, is swiftly forgotten.

All the more bizarre is then the choice of the writers choosing a side themselves, making it fairly clear who they consider to be the rightous one. Without getting into to much detail HotD falls into a trap I like to call „The Girlboss Problem“, elevating a woman into power for the sake of being a woman without analysing the problematic structures beneath, all the while making the male counterpart inherently unlikeable. Much like saying „more women as CEOs“ is going to solve capitalisms rampant sexism problem, it somehow comes to the conclusion that Rhaenrya as queen is going to solve feudalism. Time and time again we are told that she cares about the people, while also creating policies that hurt the people, like blockading the capital or leading dozens to a fiery death all for the chance of having more nukes with wings. This is somehow met with only the barest of critisim. In direct contrast all the bad decisions made by her side are done by the men counceling her.

This is not to say there isn`t some interesting storytelling to be done here. Questioning the sexist practises of having only male rulers and all the trials that come while trying to fight agains it, is interesting and also a part of the books. But the conflict is not that easy and more importantly, the confllict is not black and white. Grey is how Martin portrays his characters, with honour being found few and far between. In this vein Book-Rhaenyra also becomes a terrible person or at least a person who does appaling things for power, because once again, this conflict is not about right or wrong, its about hunger for power and the disregard of the people. Or in short: that war is bad.

This is parallel to Netflix`s Avatar: The Last Airbender where in an attempt to make the story more mature, they ended up making it worse. The role of women can be once again heralded, as in the time leading up to the release, they proclaimed to remove Sokkas sexism, as if him being sexist wasn`t a flaw to overcome (which he does) but rather just a bulding block of his character. This makes it even funnier, when they end up making Katara into a passive character, removing almost all her skill and agency. Coincidetally, both shows have been somewhat been disavowed by their creators, with Michael Dante DiMartino and Bryan Konietzko leaving the show after creativ differences and Martin publicly questioning its quality. Both of these cases can be attributed not to ego, but more to the wish of preservation, the wish for treating the stories with the respect they deserve.

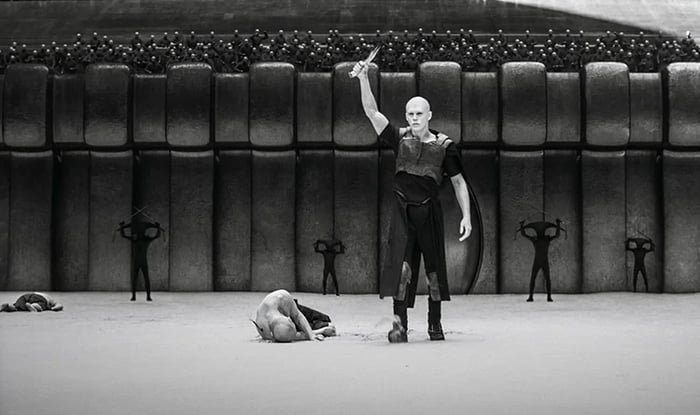

Dune: Part 2 itself struggles with the themes of dangerous and charismatic leaders, while also trying to provide a satisfactory conclusion in all its glory. This is not different to how Frank Herbert felt, while writing Dune, as to many people came away with thinking Paul was the hero, leading him to write a second book, refuting these notions. The movies beimg made with hindsight, somehow doesn´t help them, as still too many missed the point. This is, because once again spectacle is preferred, a sense of normalcy required for the adaption to be made. Dune: Part 2 cuts out a lot of plot, major characters and story elements get left on the floor, rarely being referenced. This once again can be ascribed to the weirdness of Dune, that only increases with every book moving forward. This is frustrating, because to be Dune, is to be weird, which stands in direct contrast to the machine that is the entertainment industry, that can`t bear to strive to far from what we know or are comfortable with.

The art of missing the point here is, that weird means nuance, that the complexity of the worlds that are created stems from them being unreal, often times uncanny. Adapting Herman Hesses Der Steppenwolf without the final dream sequence or the Illias without the mythology like Troy did, only does a major disservice to not only the consumer, but to the story itself. Uncanny and unreal elements enhance the story, letting the absurdity of the main conflicts stick out all the way more.

For example, in Dune there exists a character similar to Paul, a near Kwisatz Haderach, only to be cast aside after being born with genetic imperfections. This serves to show Paul`s insognificance, his fraudulent status as a prophet, a hero, however he unfortunately is an inherently weird character from the way he presents himself, but also by how others percieve him, so he is cut. In ASOIAF magic and the White Walker serve to put a contrast to the pesky squabbles of the noble houses, a higher form of power and threat that in the end renders all the wars useless, because if they come, they are gonna destroy everything and everyone. However, after years of critical acclaim and the surge of viewership, the notion, that only the politics is what made Game of Thrones great, arose. This served another blow in its historical downfall, as it abandoned the foundation the story built upon and created meaningless conflict deemed „smart politcal drama.“ This false notion swallows up other projects as well, as studios hunt for the next Game of Thrones after it`s ending results in shows like The Witcher, a complete removal of all that makes the books and games unique in service of a smart political drama, that at it`s core, misses the appeal and charm of its original.

To rectify this, House of the Dragon tries to relate the story to the White Walkers, that wait far up north. However in an interesting twistof irony, it forgets to draw any real conclusion from it. Rhaenyra, within this context, gets told about a prophecy by her father and believes herself to be the one to stop what`s coming. The show rarely comments on it and subsquently forgets all the danger that comes from the belief of being a hero, meanwhile the ASOIAF has a whole storyline dedicated to the dangers of prophecy and believing oneself to be „the prince that was promised.“ The only one who gets told, that they are insignicicant in the grand scheme of things, is her husband Daemon, resulting in the end of a fairly drawn out arc of him bowing to Rhaenyra, whose belief in the prophecy remains unshattered.

Whether or not changes are good is a different story, a discussion likely to continue until the end of time. However the nature of changes is a different matter all together. My point with all this is, that the entertainment industry in its ever increasing lust for shareholder value and profit abandons the very foundations of storytelling and artistic integrity, while misguidung and false notions of the people writing only serve to undermine those aspects all the way more. In a world going downhill, we are being served with the illusion of normalcy, the feeling of everything being fine, when it isn`t. Specatcle is created where it shouldn`t be while points get lost for a progressive stance that hardly holds up under scrutiny. It is up to us, to detect and critizize this trend, in order for entertainment to remain what it should be, authentic.

WRITTEN BY

Lars

Being brought up under deaf parents, as a partially hearing child, I have always struggeled with my search of identity. Inspired by far-distant worlds like middle earth and the tunes of Lord Huron, my goal is not only to tell great stories, but also to understand other people and their tales.